Water Scarcities, Tourism and Vaccines: The Navajo Nation’s COVID-19 Battles Through the Eyes of a Community Organizer

With the skies still standing shy of the sun, Alicia Martin is up early to get the day’s deliveries in order. As a trained chef, Alicia has worked in the restaurant industry for many years.

However, this time, she isn’t checking restaurant inventory; instead, she’s tallying up numbers of water barrels, canned food items, masks and hand sanitizer among other essentials to deliver to people on the Navajo Nation reservation in Arizona. This is because in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, Alicia decided to trade in her chef’s hat to don the hat of a community organizer.

During the first wave of the pandemic, the Navajo Nation had the highest infection rate per capita of all US states.

As of May 27, 2021, the Navajo Nation reported 30,793 positive COVID-19 cases and 1,306 deaths from the infection. For a total population that is just over 173,000, this translates to an infection rate of 17.8 percent and a case fatality ratio (CFR) — the proportion of deaths among total confirmed cases — of 4.2 percent. The CFR for the entire country has been less than half this at 1.8 percent.

While Native Americans only make up four percent of Arizona’s population, they have accounted for a disproportionate nine percent of all deaths in the state. They have been 1.6 times more likely to contract COVID-19 and have died at 3.3 times the rate of White and Asian people when adjusted for age.

VIDEO: Click the image below for a preview of the conversation I had with Navajo community organizer Alicia Martin in which she discusses how COVID-19 devastated the Navajo Nation and talks about her relief efforts during the pandemic. Here is a link to the full discussion (apologies about the horrible audio quality (I think my laptop was breaking down) and bad video quality too): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I4TOY-2405A&t=18s

COVID-19 began spreading through the Navajo Nation early and fast. “Seeing all of the devastation and deaths was extremely difficult,” says Alicia. She explains how working through it was one of the biggest challenges she had ever faced.

When the pandemic hit, Alicia says people were hearing that there was a sickness going around but didn’t quite understand what it was. Initially, translating and giving COVID-19 a name in Navajo was a bit of a challenge for officials. The name that was settled upon was ‘Dikos Ntsaaígíí-19,’ which roughly translates to the ‘Big Cough-19.’

Accustomed to assisting members of their community, Alicia and her family knew they had to act fast when the pandemic hit. From hauling water to helping transport people sick with COVID-19 to hospitals and changing tires on the rocky desert backcountry roads of the reservation, the Martin family has been and continues to remain, on the frontlines for the Navajo people.

The Race Against COVID

COVID-19 spread like wildfire across communities on the reservation due to a number of different factors. Among these were Arizona’s failure to implement a statewide mask mandate, continued tourism, undeveloped infrastructure including a lack of clean running water and hospitals in many areas, Navajo traditions of living in multigenerational homes and language barriers among others.

After leading in COVID-19 case counts, the Navajo Nation came to lead the nation in vaccinations, the only silver lining in the pandemic for the community. Recently, Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez and Vice President Myron Lizer announced that the Navajo Nation now has over 100,000 individuals fully vaccinated.

The Navajo Nation’s successful vaccine campaign is attributed to factors such as tribal sovereignty that allowed for the planning of independent methods of vaccine distribution, vaccine messaging in the native language, cultural values of protecting the elderly, local leadership leading by example, virtual town hall meetings with health experts organized by tribe leaders and offering both private appointments and mass vaccination events. Perhaps the most important catalyst was the tremendous losses and suffering that the Navajo had experienced over the past year, says Alicia.

Despite the huge vaccine success, things are more bitter than sweet for many Navajo as the vaccines came after a great deal of pain and suffering, with the loss of many lives that could have been saved.

The Navajo People

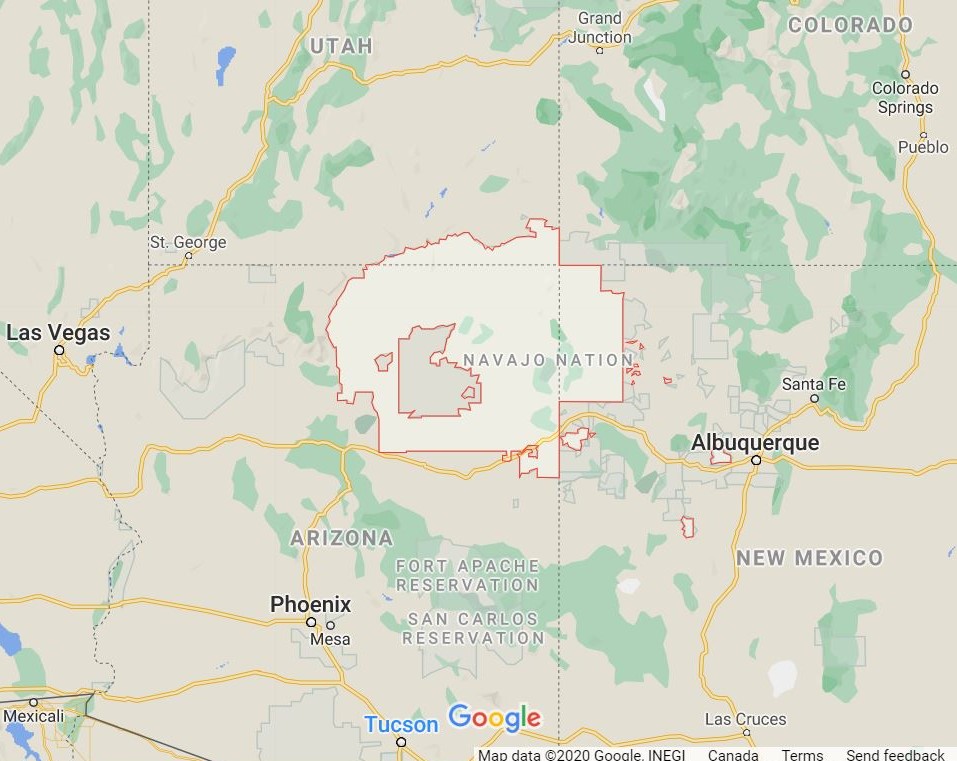

The Navajo Nation is the largest Indigenous reservation in the US by both population and land area. It is over 17.5 million acres and spans northeastern Arizona, southeastern Utah and northwestern New Mexico. Area-wise, the reservation is larger than ten US states including West Virginia, Maryland, Hawaii and Connecticut.

The Navajo people, also known as the Diné, which means ‘The People’ or the ‘Holy People’ in Navajo, live in close-knit communities across the reservation.

The Navajo Nation reservation was established by the Treaty of 1868. It came after the Long Walk, the attempted ethnic cleansing and deportation of the Navajo people, which took place between 1864 and 1866. This colonization event has come to form a large part of both the resilience and generational trauma inherent to the identity of the Navajo people today.

There are 110 different chapters across the reservation, which are akin to subdivisions or municipalities.

The Navajo Nation and COVID-19: Water Scarcities

As the World Health Organization (WHO) launched hand washing campaigns at the onset of the pandemic, many people around the world, including the Navajo Nation, were left high and dry. Approximately 30 percent of residents on the Navajo Nation do not have running water.

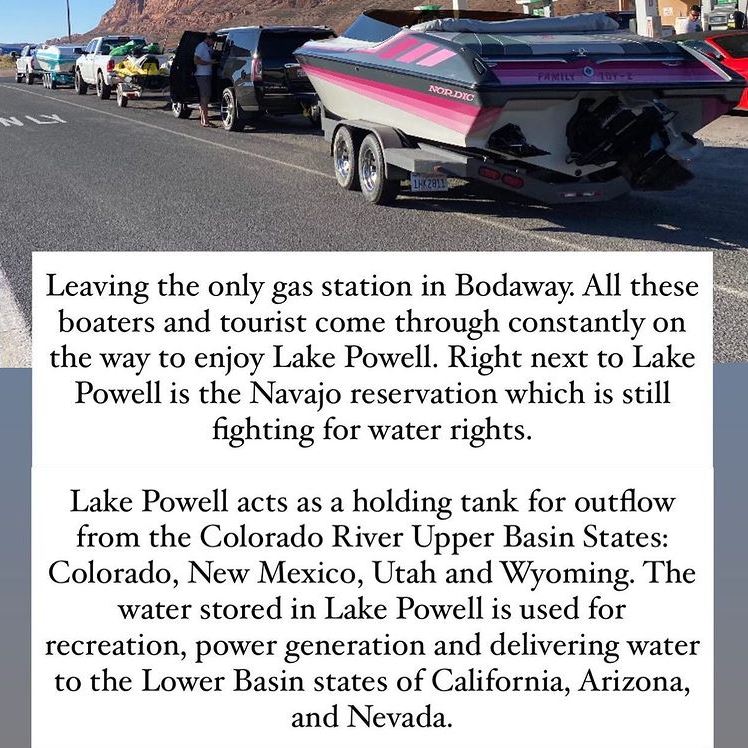

In addition to fighting for water rights, which namely includes access to waters of the Colorado River, there is the added issue of uranium-contaminated water from abandoned uranium mines across Navajo lands. Between 1944 and 1986, over 4 million tons of uranium were blasted out of the mines by mining companies.

A lack of clean running water is an obvious infection control nightmare. Many Navajo were left deciding between using their limited water supplies for drinking and cooking versus hand washing, an unimaginable and shameful reality in modern-day America.

Structural Inequities

Government policies have created socioeconomic barriers that have led to the marginalization of the Navajo and other Indigenous people in North America for centuries. This has had intergenerational impacts on social determinants of health, where structural racism has bred health inequities due to inequitable access to health services and underfunding of the Indian Health Service (IHS) system in the US. This has resulted in increased health problems such as diabetes and heart disease among Indigenous communities, which puts them at a greater risk of developing complications from things like COVID-19.

There are also systemic inequities related to environmental racism that Indigenous communities face due to restrictions imposed on land use and access to natural resources.

Despite Indigenous tribes like the Navajo having sovereignty (right to self-government) within US borders, they are prohibited from actually owning property on their reservations. This is because reservation land is held in a trust controlled by the federal government. Control of the trust is sometimes jointly shared with local tribal leaderships. Without land ownership, the Indigenous cannot build equity and develop infrastructure on the lands they live on.

Adding to this is corporate interference where big businesses buy out land and resources around Indigenous reservation areas. For example, many Navajo Nation residents look up to see power lines transporting electricity generated from dams built by mega-corporations on the Colorado River to neighbouring states such as California, as they remain plunged into darkness. The Navajo have been fighting for decades for access to the waters of the river in order to build infrastructure.

Failed tribal leaderships due to internal disputes amidst such dismal situations have only added insult to injury.

Relief Effort Beginnings

Prior to the pandemic, Alicia was researching authentic Navajo cuisines due to her background as a chef, and an interest in preserving Navajo cultural traditions by shedding light on Navajo foods.

Alicia’s community efforts began when she lost her job at a new restaurant that had opened in Page but shut down due to the pandemic. Although invited back once it eventually reopened several weeks later, Alicia was not comfortable returning because she felt the restaurant was not taking proper COVID-19 precautions.

Instead, Alicia decided to turn her eyes from the restaurant to the community. And when she looked around, she saw tremendous need.

In addition to the hysteria around toilet paper in major cities, there were significant shortages of food items at local stores in Page. Due to its remote location, things take longer to arrive in the town. Seeing this, Alicia and her family set up a food distribution drive using their savings and Alicia’s connections to a food purveyor.

Alicia describes seeing an elderly Navajo man at the drive who was looking to buy what he could with the little money he had. Someone saw this and stepped up to buy a food box for him. When given the box, the man was hugely grateful and emotional out of both disbelief and relief. That’s when Alicia says she realized how afraid people were and “how much need there was.”

Serving the community is not new to Alicia. Growing up, she was used to seeing her family coming to the assistance of people. Her father worked at the local power plant and did well, so “anything extra always went back to the community,” she explains. Alicia is also greatly inspired by her late grandmother who was well-respected within the Navajo community due to her defiance and strong will to help people.

Hauling Water

After their first food distribution, Alicia and her family began daily trips hauling water out to people across the reservation. They would transport water from Page to various areas including the Bodaway-Gap chapter, where Alicia grew up, making the journey across the dusty desert roads to deliver them to people in need, many of whom included elderly folks. Due to its remote location and the undeveloped dirt roads leading to it, the 45-minute drive to Bodway from Page can often turn into a 1 to 2-hour trek.

Along with water, Alicia and her family also distributed food, hand sanitizer, cleaning supplies, masks and personal hygiene products purchased with personal funds and money raised through Alicia’s aunt’s GoFundMe campaign called ‘Ajooba Hasin,’ which means compassion, caring and kindness in Navajo.

Alicia speaks highly of other grassroots efforts that materialized during the pandemic, such as the Water Warriors United, a water relief campaign that delivers water to communities on the Navajo Nation reservation.

Tourism Woes

The city of Page is a tourist town, serving as a central hub from where people typically branch off to visit some of nature’s gems in the region such as Monument Valley, Lake Powell and the various canyons in the area.

For a community already grappling with limited resources and water disparities, tourism to the area was only making matters worse.

Alicia explains that to get to Page, tourists tend to cross through reservation areas, stopping to shop at the same gas stations and the few, small grocery stores that the locals shop at.

Tourists potentially bringing in the virus and mingling with locals in this way was putting an already vulnerable Navajo population at even greater risk.

“We compare it to the movie Jaws where they didn’t want to shut down the beach and then more people got killed. It’s the same thing here,” says Alicia.

Lockdowns and Disconnects

As Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez implemented some of the strictest lockdowns and stay-at-home orders in the country to help control the spread of COVID-19, the story was very different when it came to the former Mayor of Page, Levi Tappan. The mayor did not implement a mask mandate in the town until July, months after the pandemic began, despite continued outcry from the Navajo community. Restaurant dining also remained open during much of the pandemic.

“We compare it to the movie Jaws where they didn’t want to shut down the beach and then more people got killed. It’s the same thing here,” says Alicia.

Instead, Tappan and the city were requesting Navajo Nation President Nez to open up tourist attractions on Navajo lands, including the Navajo side of Lake Powell.

“Our people are dying and opening up the lake is the last thing we’re worried about, so it wasn’t well-received by the Navajo people,” says Alicia.

In reference to the tone-deaf request, someone posted a picture of President Jonathan Nez on social media and commented that, “He is busy fighting hard for our people.” Mayor Tappan responded to the picture by posting one of his own showing Native Americans in Page, saying, “I wish he would battle alcoholism as hard as COVID-19.” Tappan’s comment sparked outrage, with calls for him to step down after the racist remark. Alicia says he also blocked her on Facebook after she tagged him in a few posts relating to the dire COVID-19 situation that the Navajo were facing, in hopes that he may want to help.

Alicia talks about how she feels “there is a disconnect between the Navajo people and some of the White people in Page because a lot of them don’t take COVID seriously.” She says it may be because they don’t have Navajo friends and [weren’t] hearing about the deaths, even though “they’re right here, in the same town.”

“There’s a lack of unity between the people,” she says.

Given the lack of measures from the city and the state, healthcare workers and President Nez have acknowledged that it is community grassroots efforts, like that of Alicia and her family, the Water Warriors and many others, that greatly contributed to bringing COVID-19 numbers down on the Navajo Nation. Numbers even hit zero in early September of last year after the first wave.

COVID-19 Spread: Barriers and Challenges

Navajo culture is rich with traditions that foster kinship and community, such as shaking hands and readily inviting people in for a meal. However, many of these traditions have not been amenable with respect to the pandemic.

Alicia explains that Navajo traditions involve sharing bowls of water for hand washing and drinking. Moreover, for those who don’t have running water and get water in barrels and totes, people take turns siphoning water out from them through an attached hose using their mouths. But pre-pandemic, these practices weren’t “life or death” says Alicia.

Seeing the issue, Alicia and her family started buying water pumps with siphons and water sinks for families on the reservation.

Communication during the pandemic was also a problem as some Navajo, particularly older generations, do not understand or speak English. They also don’t have electricity or Wi-Fi so they can’t watch the news on TV, access the internet for information or apply for government assistance, explains Alicia.

Many Navajo people sell jewelry to tourists on side roads and are able to make decent livelihoods from it. However, because of the pandemic, that was halted and people were left stranded, waiting for stimulus cheques that were difficult to apply for and slow to arrive.

Many Navajo people were accustomed to going into offices and Chapter Houses (administrative offices or meeting places akin to a ‘city hall’) and speaking to someone in Navajo for assistance. However, many of them abruptly shut down due to the pandemic, which made applying for government stimulus programs a challenge. In addition, of the 110 chapters on the Navajo Nation, about 70 don’t have street names or numbered property addresses. This is a huge barrier to things such as elections voting and applying for assistance.

Moreover, Indian country was initially left out of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act, the $2.2 trillion economic stimulus bill passed at the beginning of the pandemic. The Navajo Nation had to file a lawsuit in order to get access to the stimulus funds.

Alicia also describes how almost her entire family came down with COVID-19 early on during the pandemic. This included her father, stepmother and siblings.

Alicia says it was tough and when her dad was in the hospital, she says she tried to keep the mood light and happy because she believes you need to “keep the mind happy and the spirit strong” to be able to recover well. These are values and ideologies that are a big part of Navajo culture.

While Alicia’s immediate family members all recovered from COVID-19, others were not so lucky.

Alicia lost a friend she went to high school with to COVID-19, who died along with his dad and grandfather. “That was three generations of men,” she says. “He left behind a son who struggles with losing his father, grandfather and great grandfather, all at the same time.”

Among family, Alicia’s dad lost his aunt, her husband and their adult daughter Sharon. All three of them passed away within two weeks of each other. Alicia’s Aunt Sharon had Down syndrome and “people with Down Syndrome are the best people ever,” she says. While it was tough for the whole community because they were all really tight-knit, Alicia says there was also some relief that they left together as it would have been difficult for Sharon to have been left on her own.

Healing from COVID-19 and Beyond

COVID-19 offered a harrowing glimpse into the disenfranchisement of the Navajo people.

Alicia says, “This is not the first crisis that we’ve gone through. Our people have gone through the Long Walk and other things. Every generation has gone through things.”

Alicia says she initially coped with the losses of the pandemic by focusing on relief because otherwise, “it’s too much.” She says, “it becomes like a war zone mentality.”

For Alicia, people looking out for one another served as her inspiration and motivation during the pandemic. She also says “to have my grandmother’s legacy continue for the people, that’s a beautiful part of it.” Alicia explains she and her family want to empower people and don’t want them to be dependent on anyone including them or the government.

Alicia also urges people to research the people they’re voting for because these are the people who will be deciding whether or not there will be a stimulus cheque to help people stay home. If there is no support, “it’s just going to create more of the same poverty and losing more people,” she says.

Although donations have been steadily pouring in, the need has been great. Other Native American tribes in the area were also in great need and Alicia feels, “It’s hard because [when they ask for help] we’re not going to say no. So the more stuff we get, the more stuff we can share.”

And the need doesn’t stop with COVID-19. With seasonal work and a lack of infrastructure and resources, many families struggle to get by, living in homes without insulation and lack of firewood in the winter to keep warm.

Alicia also encourages people to start following Navajo people on social media, do research and just dive in and start helping. This is the best way to learn, she says.

Despite the worst of the pandemic having passed, the mourning, grief and reflections will continue for months, if not years, to come. Alicia says it’s almost “strange to not be working in crisis mode anymore and to have to deal with the emotions and the impacts on mental health.”

Time will of course be a factor in the healing, as well as acknowledgment and accountability. Social injustices against Black and Asian people have come to the forefront during the past year and it is high time that Indigenous communities be acknowledged the same.

The cycle of racial injustices and the disproportionate impact of crises on marginalized communities must be broken. Patting people on the back for their resilience in the face of atrocities instead of holding perpetrators accountable, is a pattern of injustice and induced trauma that must be broken.

While vaccines will hopefully help the world see the end of COVID-19 soon, we must work collectively to end the plagues of systemic injustices and marginalization in much the same way.

To learn more about the Navajo people and contribute, you can check out Alicia Martin on Facebook and Instagram @amartin2727,

and

the Martin family relief effort campaign “Ajooba Hasin” on Instagram: @ajoobahasin

You can donate to the relief efforts through PayPal: https://www.paypal.com/paypalme/ajoobahasin

You May Also Like

The Grand Canyon: A Historic Junction of Science and Culture

November 12, 2020

PREVIEW: The Navajo Nation’s COVID-19 Battles

December 23, 2020